Bicycle Helmet

Campaign Guide

Summary: A guide to community bicycle helmet campaigns. It will provide good ideas even if you don't care to undertake the whole program.

Original author: John Williams

Then of Bikecentennial/Adventure Cycling,

now with Tracy-Williams Consulting

Original publisher: North Carolina DOT Bicycle Program, 1991

Updated by: Bicycle Helmet Safety Institute, 2002

(This copy current on August 27, 2006)

Contents

1. Bicycle Helmet Campaigns

Want to do something about bicycle safety in your town? Why not mount a bicycle helmet campaign?

- Introduction

- Ideas for Campaigns

- Crash Facts

2. All about heads and bicycle helmets

Before discussing details of bicycle helmet campaigns, let's first look at some important aspects of helmets and answer a few basic questions.

- Aren't helmets just for serious riders?

- What's so special about head injuries?

- What the research says.

- How can bicycle helmets help?

- What makes up a helmet?

- How can I be sure a helmet is tough?

- What about comfort and weight?

- How much does a helmet cost?

- Will people wear helmets?

- Parents tips on helmets: Choosing, Fitting, Persuading to Wear.

3. Organizing a local bike helmet campaign

Putting together a successful bicycle helmet campaign takes organizing skills and a commitment to seeing things through. Here's how!

- Select a target age group

- Set your project goals and objectives

- Using a steering committee

4. Creating your campaign

Creating your campaign requires making a number of key decisions and carrying through on your commitments.

- Choosing a time-frame

- Deciding how long it will run

- Setting the timetable

- Finding money and supplies

- Recognizing volunteers and sponsors

- Evaluating the results

- Planning future campaigns

- Choosing campaign messages

- Popular helmet campaign messages

5. The pieces of a campaign

Each campaign contains a number of elements. Some may have only a few, while others include a wide variety of projects.

This manual focuses on helmet safety, but be sure your messages and materials place helmet promotion as only one part of bicycle safety.

- Creating displays

- Rewards for helmet use

- Cutting helmet prices

- Making direct contacts

- Suggested outline for a PTA presentation

- Demonstrations

- Getting media support

- Distributing helmet promotion materials

6. Appendices

6A. References and Contacts

6B. Sample survey

6C. Sample budgets for helmet projects

6D. Case Study #1: Seattle, Washington

6E. Case Study #2: Pitt County, North Carolina

6F. Case Study #3: Palo Alto, California

6G. Case Study #4: Madison, Wisconsin

6H. Case Study #5: Missoula, Montana

The original version of this Campaign Guide was produced by the North Carolina Department of Transportation Bicycle Program in cooperation with the Department of Environment, Health, and Natural Resources Office for Prevention, the Center for Disease Control, the University of North Carolina Highway Safety Research Center and the State Office of 4-H and Youth Development. Text, layout, and information were developed by John Williams, then of Bikecentennial, which has become Adventure Cycling. When this manual was written John was with Tracy-Williams Consulting, and they had an amazingly useful web page for bicycle planners. The case studies in this manual were written by Gary MacFadden of Adventure Cycling and Kathleen McLaughlin. Funding for the original project was provided by the Federal Highway Administration through the Transportation Improvement Program. The manual was updated and posted on the web by Randy Swart of the Bicycle Helmet Safety Institute, without funding from anybody, but with help from John Williams, in 1997. It has been updated several times since, with a refresh date at the bottom.

California's manual for school-based programs

If you are conducting a school program, you should check out the Safe Routes to Schools page by the State of California. Some of it is California-specific, but it will be worth your while to check it out. The material below will still be useful, no matter what your campaign target is.1. Bicycle helmet campaigns do good things.

Want to do something about bicycle safety in your town? Something that can save lives and prevent many needless injuries?

Why not try a bicycle helmet campaign! Bicycle safety has many parts, but there are few things that can make as much difference in a bicyclist's safety as a helmet. Unfortunately, many people don't know how important one is. They may not have ever tried a helmet on or seen one up close. Others have just not thought about helmets, think they are expensive, or have been postponing a decision. That's where you come in!

A bicycle helmet campaign ties in well with the current concern about reducing obesity. Schools and health departments are looking for ways to promote healthy physical activity for both youth and adults. Keeping your weight within a reasonable range is important for health, and bicycling can help. Bicycling safely and wearing a helmet while you bicycle are important too. The concerns can be addressed together.

A good bicycle helmet campaign will educate the public--children, parents, adult bicyclists--to the need for head protection. In many communities, this means overcoming apathy. While that may not be easy, the results are gratifying. Seeing the need for head protection often raises other questions about how to make the cycling environment safer.

Once people see the need, they must be able to get helmets. Although this is not an issue in many communities where good quality helmets are available at low cost from retail outlets, some campaigns work with local bike dealers to arrange good deals on quality helmets. In addition, many pursue special campaign prices and, in some cases, print discount coupons for consumers.

The bottom line, however, is results: saving lives and preventing serious injuries. And it's been shown that bicycle helmet campaigns can have a real effect on safety and injury prevention.

A study from the Harborview Injury Prevention Center in Seattle, Washington, found that bike helmets could prevent three out of four cycling deaths. A follow-up study published in 1996 and available on the Snell Foundation site if your Internet connection is up, confirmed that. And one state's helmet campaigns led to a 20 percent drop in hospitalization due to bike-related head injuries.

What do people do in their helmet campaigns? Here are five ideas that have increased awareness of bike helmets:

- A PTA leader got local bike shops to donate sample helmets for use in school bike safety programs.

- A Safe Kids Coalition got a major manufacturer to offer very low prices on helmets sold in local schools.

- A bicycle program got together with the few kids who wore helmets and the local TV station, and filmed several bike safety Public Service Announcements.

- A parent put together a safety-and-helmet puppet show and took it to all elementary schools in town.

- A local radio station's disc jockey gave away prizes to all helmeted riders he saw while driving around town.

- A church program was supported by the minister, who wore a bike helmet while preaching his sermon!

Why not get involved in promoting bicycle helmet use in your area? Helmets really do make a difference!

Eight Sobering Bicycle Crash Facts

Nationwide:

1. About 800 Americans die each year in bicycle crashes.

2. Using a helmet could save about 680 of them.

3. About 500 are younger than 18.

4. Over 500,000 visit a doctor after a bike crash.

5. Only about 5% of all serious bicycling injuries involve cars.

6. 40,000 injury-producing bike-car collisions are reported.

7. About 40,000 more go unreported.

8. Most car-bike crashes happen on quiet neighborhood streets.

Those are shocking numbers: riders need helmets now! Then we need to work on the road environment to make it safer.

2. All about heads and bicycle helmets

Before discussing bicycle helmet campaigns, let's first look at some important aspects of bicycle helmets and answer a few basic questions.

Aren't helmets just for serious riders?

Bike helmets are for all riders. Nasty bicycle crashes can happen to anyone, anytime, anywhere, and at any speed. Parents may think their children are safe riding around the neighborhood. But research tells us that most serious bicycle crashes occur on quiet neighborhood streets. This is especially true for young children. And nearly 30% of all cycling deaths happen on residential streets.

In addition, even simple falls can lead to life-threatening injuries. According to a study of North Carolina emergency rooms, one out of four serious bicycling injuries is a head injury. And roughly one out of three head injury crashes don't involve cars.

In about half of all bicycling crashes the rider's head hits a solid object: perhaps a car, the pavement, or a curb. Such crashes can easily cause brain or skull damage.

What's so special about head injuries?

Nationwide, nearly 50,000 bicyclists suffer serious head injuries each year. Many never fully recover. Broken bones or "road rash" can heal readily but a head injury can lead to death or disability.To understand why, lets look at the brain and how it's protected. What follows is condensed from a brochure from the United States Cycling Federation.

The outermost layer of the head, the scalp, is the first line of defense; underneath this is the hard bony skull. The brain itself floats in cerebral spinal fluid, a slippery liquid, and is surrounded by a thin membrane, the dura. The brain joins the spinal cord at the brain stem. Through this junction, messages pass from the brain to the body and back again. The brain is the control center for the body and, as a result, brain damage can affect how--and if--a person's body works.

There are three main types of brain injuries: concussions, contusions and hemorrhages.

Concussions happen when the brain gets "shaken up" and stops working for a while. Usually, things soon return to normal. However, in a severe concussion, permanent damage can occur.

Contusions are bruises caused when the brain hits the rough inside surface of the skull.

Hemorrhages happen in severe cases, when the brain bleeds. If this happens, the brain can get squeezed because there's no place for the blood to go in the closed skull. This internal bleeding can easily lead to death or permanent brain damage, even though the cyclist may seem ok for days or weeks.

In addition, the skull may be fractured. While a skull fracture might not be serious, pieces of bone may pierce the dura and damage the brain.

Because the brain is so important, even mild injuries can cause serious problems. Loss of memory, increased irritability, odd changes in personality, inability to hold a tennis racket... these and many more things can happen to people who hit their heads in a crash.

What the research says

Findings of a study reported in the Cochrane Collaboration in 2009:

Bicycle riders with helmets had...

- Helmets provide a 66 to 88% reduction in the risk of head, brain and severe brain injury for all ages of bicyclists. Helmets provide equal levels of protection for crashes involving motor vehicles (69%) and crashes from all other causes (68%). Injuries to the upper and mid facial areas are reduced 65%.

- Helmets reduce bicycle-related head and facial injuries for bicyclists of all ages involved in all types of crashes, including those involving motor vehicles.

Conclusion: Bicycle safety helmets are highly effective in preventing head injury and are particularly important to children, since they suffer the majority of serious head injuries from bicycling crashes.

How can bicycle helmets help?

The brain needs protection. When a person rides a bicycle, the best protection comes from a bike helmet.A bicycle helmet can't keep someone from falling off a bike. It can't keep a car from hitting you. But it can cut the chances of serious brain injury. It does this by cushioning the blow that otherwise would hit the skull and brain in a crash. In doing so, the foam liner of the helmet is crushed between the object (car, curb, roadway) and the rider's head; in other words, it "self-destructs" in order to protect what's inside. The foam in most helmets does not recover. This is why any helmet that has been crashed should be replaced and not used again, even if it appears to be in good shape. There's no way for the user to tell just how much protection is left. (A few helmets made of a special foam called EPP for Expanded PolyPropylene do recover, and can be used again.) We have never heard a rider who trashed a helmet in a crash complain about the cost of replacing it!

We know that helmets do protect. As noted above, researchers say that bicycle helmets could prevent between 63 and 88 per cent of all serious head injuries to bike riders. And, since about 75% of all cycling deaths are due to head injuries, helmet use could save many lives each year. That's a worthwhile investment for any bicyclist, young or old.

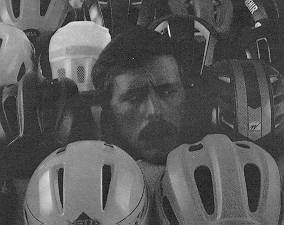

What makes up a bike helmet?

What makes up a bike helmet?Every bicycle helmet contains a dense liner made from stiff crushable foam. This liner crushes and manages the impact energy in a crash. Most helmets protect this liner with a plastic shell, which helps hold the foam together in a crash and improves the slipperiness of the helmet so it will not "stick" to the pavement. The straps and buckle keep the helmet from flying off during a crash sequence before the rider hits the pavement. There may be a stabilizer in the back as well to improve the helmet's stability while riding, but the strap does the work of holding the helmet on in a crash. All parts of the helmet work together to prevent injury.

Keep in mind that for a helmet to work properly, it must fit and be adjusted correctly. If it is out of position when the rider hits, bare head may be exposed to the impact! See Parent's Tip #2 below for information on correct size and fit. And check out this page on how hairdo's and baseball caps affect fit.

How can you be sure a helmet is tough?

All helmets sold in the U.S. since 1999 must by law meet the standard published by the US Consumer Product Safety Commission. There will be a sticker in the helmet certifying that it meets the CPSC standard. That means it meets impact and coverage requirements.

The CPSC tests require putting metal headforms inside the helmets and dropping them on hard surfaces. The helmets must manage most of the impact, allowing only a small amount to get through. Helmets that don't pass don't get certified.

Consumer Reports tests bicycle helmets every two or three years. Their articles never include as many models as we would like, but they are the only independent source of published performance ratings, so we have included our review of their latest article on this disk.

What about comfort and weight?

Today's bicycle helmets weigh between 7 and 14 ounces-about as much as a wool sweater. This is much lighter than the helmets sold back in the 90's. Since helmets have been required in bicycle racing in the U.S. since 1986, manufacturers have worked hard to cut the weight of their models, and to increase ventilation. That's an improvement that has benefited everyone.

Weight is also important for infants riding in child seats; their necks could be strained by heavy helmets. As a result, infant helmets are designed to be very light as well, even though they have increased coverage.

With older kids weight probably isn't as critical as durability. But the perception of a light helmet is important to almost any user. Riders of any age just will not use a helmet they think of as heavy.

How much does a helmet cost?

Bicycle helmets are cheap! In the 1990's prices dropped like a stone. The manufacturers are still crying the blues, but for consumers it has been a buyer's market ever since. You can still pay way over a hundred dollars for a helmet if you want the latest thing that a hero used in the Tour de France, but in discount stores it is not unusual to find decent helmets at $10 to $25, and even in bike stores there is usually a fine helmet around $30. Bike stores offer a valuable service: they will fit your helmet properly. That's worth a lot, since fit makes a big difference in how much protection a helmet gives you. But helmets are available for helmet campaigns at very low prices: check out our latest update on inexpensive helmets for more info.

The Bicycle Helmet Safety Institute submitted samples of six helmet models to a leading U.S. test lab: three in the $150+ range and three under $20. The impact test results were virtually identical. There were very few differences in performance among the helmets. Although the sample was small, the testing indicates that the consumer can shop for a bicycle helmet in the US market without undue concern about the impact performance of the various models, whatever the price level. The most important advice is to find a helmet that fits you well so that it will be positioned correctly when you hit.

We never want to lose sight of the fact that what a helmet protects is priceless: a cyclist's life and future. But lower priced helmets can make all the difference in a successful helmet campaign!

For those who have suffered brain injuries, rehabilitation is a very costly and difficult challenge. Here are some facts from the National Head Injury Foundation:

- Each severe head injury survivor requires between $4.1 million and $9 million dollars in care over a lifetime.

- The typical survivor of severe head injury requires between five and ten years of intensive rehabilitation.

- There are 2,000 cases of persistent vegetative state in the United States every year caused by head injury.

While facts are useful, they don't measure the personal cost. Here is what Mark Guydish of the Velonauts Bicycle Club said about his brother's tragic traffic accident:

Michael's accident, his transformation from a kind, young vibrant man to a stuporous, childlike being in need of long, hard therapy, has taught me one lesson acutely: there is nothing greater a human being can lose than a mind, and nothing he should value more.

Compare these costs--in terms of both dollars and human suffering--with the cost of a helmet and you will see how good a bargain a helmet is. Remember, too, that a good helmet will last for years, as long as it's never crashed. That's more than you can say for a pair of sneakers!

Will people wear helmets?

Starting a new safety habit can be hard, both for the individual and for the group. That was true when they brought in hockey helmets, football helmets, motorcycle helmets, and many other protective measures. And it's true now of bicycle helmets. In a typical town, it will take time to make helmets popular. One study, done in Wisconsin, found that few bicyclists had thought about wearing a helmet. Another survey, done in Pitt County, North Carolina, found very few who wore bicycle helmets.

But times are changing. Nation wide, several million bicyclists now own and wear helmets when they ride their bicycles. With gentle but firm encouragement, more will join the growing helmet movement. In some communities with active helmet encouragement programs, helmet use has grown from less than one percent to over 35 percent. The program in Seattle, Washington, is perhaps the best known and has enjoyed enormous success. There, more than 65 percent of all bicyclists wear helmets. There are active local programs in many other communities. Safe Kids USA mounted its second national bicycle helmet campaign in 2002. If you are working with kids and have a local Safe Kids Coalition they can be a source of help.

Parent's Tip #1: Choosing a Bicycle Helmet

Make sure it can be adjusted to fit. Fine tuning the fit with foam pads and strap adjustments should make it fit snugly but not be tight. It should sit level on the head and shouldn't rock from side to side or front to back.Make sure it meets the standard. Look for a sticker inside that says it meets the CPSC standard. (Required by law for a bike helmet.)

Make sure it has adequate ventilation. Kids using BMX or skate helmets don't seem to care about sweaty heads, but the rest of us need adequate front vents to permit air flow.

Make sure the child likes it. It's a lot easier to get a child to wear a helmet if he or she helped pick it out and likes it. If they think it's geeky, you may have helmet wars!

Remember: helmets aren't forever. Since a helmet uses itself up saving your child's life, it makes sense to replace it after a crash. You may not even be able to see the damage but it's better to be safe than sorry. And at some point, your child may outgrow a helmet. Heads grow less than arms and legs, and you can extend its life by using thinner sizing pads, but the time will come. The Maine retrofit program can help with ideas for extending helmet life.

Is it important to keep the head cool?

Bicyclists are their own engines and produce heat; a lot of this heat radiates out through the head. As a result, helmet ventilation is important--especially on long rides on hot days. It's possible to get overheated and dizzy while riding in the summer heat with a poorly-ventilated helmet. For this reason, bicyclists who do more than neighborhood cruising or riding to school should look closely at how well the helmet cools. All current helmets have slots or holes to let in air. Although the number of openings may be a sales point, it is mostly the size of the front vents that determines how cool a helmet will be.

Some toddler helmets don't have ventilation. That may be ok in mild weather, since the child is most often carried in a child seat or trailer and isn't as likely to overheat. But in warm weather a toddler needs ventilation too.

Some BMX racing helmets do not have ventilation either. BMX events are short, and the kids like the motorcycle helmet look, so they don't insist on vents. Skate helmets have minimal vents, but again the kids insist on the style.

What about looks and fashion?

Way back in the 80's, bicycle helmets looked like buckets or ugly mushrooms. They were hot, often uncomfortable, and weighed a ton. But not today! Using modern materials and designs, manufacturers have created protective helmets that look great, feel light and cool and protect better! They come in all sorts of fashion colors with great looking covers and graphics. Some come with stickers your child can use to personalize them. And there's a style to suit nearly everyone.

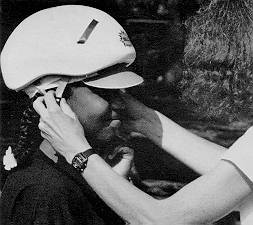

Parent's Tip #2: Fitting your child's helmet

1. First, get the right sized helmet. Helmets come in sizes from Small to Extra Large. Each size fits a range of head sizes. Find one that fits comfortably and doesn't pinch. Let your child try the helmets on.

2. Use the sizing pads for a comfortable fit. Most helmets come with different sized foam pads. Use these to "fine tune" the helmet's fit to your child's head shape.

3. Finally, adjust the straps for a snug fit. The helmet should sit level on the head, cover the forehead down to the eyebrows and not rock back and forth or side to side. Helmets have adjustable straps to help you get them level and snug. The adjustments are fussy, so be prepared to spend a few minutes doing it.

Parent's Tip #3: Taking care of your child's helmet

1. Be careful using paint or stickers on a helmet. Some paints and stickers can damage a bicycle helmet. Don't use anything on it unless you are sure it's safe. Some bike shops sell bright reflective stickers that are safe on helmets. Check them out!

2. Clean the helmet with gentle soap and warm water. A helmet gets pretty dirty over time and it's nice to clean it up. But don't use solvents or cleansers! These can damage the helmet, even though the damage might not be visible. Hand soap or dish washing liquid are fine.

3. Treat a helmet with respect and care. While a it is made to take knocks, excessive abuse can damage it. It's best not to waste its strength by tossing it around or kicking it.

Parents Tip #4: How to get a child to wear a helmet

A bicycle helmet may take some getting used to at first. Even the lightest models may not feel natural until the rider gets used to wearing them. These tips will help parents encourage the helmet habit in their children.

1. Let your child help pick out the helmet. After all, he or she is the one who will be wearing it. If your child enjoys decorating personal items, look for one of the helmets that comes with stickers they can apply, or buy some helmet-friendly stickers separately. (Unfriendly stickers have aggressive adhesives that can damage a helmet's shell.)

2. Help your child learn to use the buckle. Helmet straps may be difficult for young fingers. Help your child practice until he or she can buckle and release them easily.

3. Always insist your child wear the helmet when riding. Anyone can get hurt on a bike anywhere. Firm rules are usually needed for any safety practice.

4. Always insist your child remove the helmet when they arrive at a playground or climb trees. Helmets can snag in the equipment or on a tree limb and strangle the child.

5. When you ride together, wear your own helmet. Your own good example can make a big difference in encouraging your child to wear one.

6. Praise and reward your child each time. Your youngster may feel strange at first wearing a helmet. You can take away some of the discomfort with words of support.

7. Begin the helmet habit with the first bicycle. Make it a firm rule and it will become a habit as your child grows, just like buckling up a seatbelt in the car.

7. Encourage other parents to buy helmets. Making helmets normal is the best way to eliminate the discomfort of being "different."

Parents Tip #5: Playgrounds and Helmets Don't Mix!

In 1999 a Pennsylvania child strangled and died in a piece of non-standard playground equipment while wearing a bicycle helmet. He was caught between two overlapping horizontal platforms when his helmet would not fit through the gap between them where his body had already gone. Here is more detail on playground equipment problems. Trees have no standards for branch gaps, so don't let your child climb trees with a helmet on either, even though it may seem like a good idea!

Summary

All in all, today's bicycle helmets are inexpensive insurance against the tragedy of serious head injury. They are lightweight, inexpensive, come in a wide variety of colors and designs, and provide good ventilation. Wearing a bicycle helmet makes good sense.

Check out this page on the disk if you need a simple explanation of how a helmet works.

3. Organizing a local bicycle helmet campaign

To promote bicycle helmet use, you need a plan. You must decide who to reach and how to do it. The following sections take you step-by-stop through this process. Along the way you will make important decisions shaping your campaign and fitting it to your community's needs and resources. The overview below gives you a basic outline for designing a campaign. Look it over and then browse through some of the ideas on the following pages.

Overview

This section is organized into the following topics.

- Select a target age group. Which age groups ride the most? Which age group is most at risk? Who wears

helmets now? Who should be the campaign target?

- Set your project goals and objectives. Build campaign momentum. Raise awareness of bike injuries and head

trauma. Increase helmet purchases through greater availability. Increase helmet use. Reduce the number and lessen the

severity of head injuries.

- Using a steering committee. Build a coalition, hold successful meetings and involve your committee

members.

There are few hard-and-fast rules on just how to do bicycle helmet promotion. Some people, for example, print discount coupons and distribute them in the schools, while others rely more on television and radio to spread the word. Some get local groups to donate money for helmets, while others go straight to the manufacturers for special discounts. Some put together coalitions of health-related groups, while others work alone or with one or two helpers. Some work only with the PTA. Some police departments have good success with bicycle rodeos. At least one local campaign involves organized religious groups.

Whichever approach you take, keep in mind that a good campaign uses a variety of means to its end. A campaign that relies strictly on coupons or TV or school presentations will not have as much impact as a campaign that combines these elements.

As your campaign gains momentum, you'll find many opportunities to get your message across. Take advantage of these opportunities as they arise. Keep in mind, too, that changing people's attitudes on safety takes time. You may not achieve your goals in the first few months. But if you keep at it, you'll find success.

Select a target age group

One of your first decisions will be to choose a target group. Ask yourself just who you want to reach. This is an important decision because it affects many future choices including how best to reach that audience. How do you decide? Ask yourself the following questions:

Which age groups ride the most?

In some communities, there is a large adult cycling population. In others, elementary school kids are the only ones who ride. In still other areas kids are not allowed to ride much due to traffic and security concerns. Your bicycle shops, police or recreation departments may have some ideas. You may be able to find local bike use survey data. This is particularly true if the recreation department has gotten Federal Land and Water Conservation Fund grants from the State; recreational surveys are required.

If you don't have a survey, why not do one? Recruit a high school or college class to do it for you. See the appendix for a sample survey. If you can't afford the time or effort a survey requires, start off by guessing what your biggest group will be. Your own observations around town, coupled with those of other safety advocates, should give you a good start. Later, do the survey.

Which age group is most at risk?

Emergency room doctors and nurses can help with this question. They see who comes in with bicycle-related injuries. Police data may help too, but keep in mind that typically fewer than 20% of all serious bike crashes are reported to the police. Use the general categories listed below. As a start, statewide 10-14 year olds are the age group most at risk, according to a report from the University of North Carolina. Studies consistently show that males are more at risk than females.

Who wears helmets now?

Before you set goals on increasing helmet use, you need to know how many people (and of what age) wear them now. You can get this information through a phone survey or by counting bicyclists at several places around town. Pitt County, for example, conducted a telephone survey during the early stages of their project to determine how many kids wore helmets. North Carolina did a state-wide survey in 2001 and found only 17 per cent of their riders using helmets.

Bike counts can be very useful for several purposes and are a good use of volunteer time. Pick count locations where you can see a good assortment of bicyclists. A major bike route that passes near a school and a park but also serves adult commuters might be a good location. Count bikes from 7 AM to 7 PM on a weekday and the same period on a weekend. These records will be invaluable when it comes time for project evaluation, a key component of your helmet campaign. Here is an evaluation program designed in New York State so you don't have to reinvent that wheel.

Who should be the campaign target?

Once you have some ideas of who rides, who is most at risk, and who wears helmets, you can decide which group is going to be the first target for the campaign. Keep in mind that the target group may be best reached indirectly. For example, young kids may be best influenced through their parents or teachers.

Although there is a tendency to focus on age groups, there are other populations that are worthy of your consideration as our communities have become more diverse. Many urban helmet promoters have observed that helmet use is high in the affluent suburbs and low in the inner city, cutting across all age groups. Recent immigrants from countries where bicycle helmets are a novelty may be another target group in your area. Reaching such groups may require tailoring your program in a radically different way. At a minimum, you would probably want some Spanish language materials in many areas. It may also be desirable to work through ethnic groups or organized religious groups to reach particular immigrant populations. If you can pull at least one of these people into your campaign organization they can provide more ideas for the specific group that may never occur to you.

Get help from members of your target audience in choosing among possible messages. Pick five to ten candidate messages and show them to a number of people in the age group you want to reach. Ask them to tell you which make the most sense, which are confusing, which are convincing and which are weak. While you are at it, dig for info on where the messages might be most effective, and what kinds of promotion events your target age group might participate in.

Going through these questions may take some time. They require information, something you may not have at the start. But they will give you a sense of direction and provide information you can use in news releases and campaign literature.

You may change primary target audiences as your campaign progresses from year to year. And, while it's important to focus on a specific age group, try to produce some information for all ages. It's best not to give people the impression that only little kids, for example, need bicycle helmets.

Some tips on target age groups

Helmet campaigns from the U.S. and abroad have taught us the following about the different possible target audiences. Most campaigns have been directed at either kids or their parents.

Pre-school: Direct your messages mainly at parents and focus particularly on the importance of helmets for youngsters being carried in child carriers; these children are particularly vulnerable. Also discuss how adults should wear helmets themselves in order to be good role models for the kids.

E1ementary school: Again, direct messages mostly at parents. Focus on the importance of helmets for kids riding around the neighborhood. Emphasize that falls can cause serious head injuries and also mention that parents should be good role models. Some straightforward messages directed at youngsters should help as well, particularly when delivered in school classes or assemblies.

Junior high school: One of the toughest potential audiences. Parental influence is less powerful and peer pressure, fashion, and one's personal image are more important than for younger students. Be careful of messages that adults think will be cool. Kids need straight talk from people who really know their stuff. Emergency Room doctors and expert cyclists--especially high-school aged cyclists--would be good.

High school: Another tough audience. Peer influence is more powerful yet. Again, they need straight talk from experts, preferably young ones. If helmet use becomes common only among the very young, expect older kids to balk at wearing them. Some laws require riders under 15 to wear helmets. When you turn 15 do you want to look 14?

College: Most campaigners have found it difficult to reach college-age adults. However, they are an important age group to consider, due to their influence over teen-age cyclists. General community campaigns (such as the Madison, Wisconsin, project mentioned in the appendix) may work and tend to focus on being a "well-dressed" cyclist--with a helmet. However, direct college student involvement should be better. Among collegiate club cyclists, requiring helmets on rides is a common approach. Serious safety messages may also work (e.g. in the campus newspaper). The Bicycle Helmet Safety Institute has found that since virtually all college students have access to the Internet, putting up a page on the web is an effective strategy for reaching them. If the page has enough factual content to provide easily accessible material for class papers, projects and speech class exercises, students will use it for research. Often this process puts the message before other students as papers are discussed or practice speeches are given in class. And if you educate a young person, they will be around a long time. So working with students of any age can be rewarding.

Middle age: This age group should be most likely to respond to logical arguments about the seriousness of head injuries. Virtually the same arguments that can be made for life insurance and seat belts should work for this group. They are generally still swayed more by fashion than by logic, but for them, fashion may include embracing a safety campaign that demonstrates their rationality and concern for their own or their kids' welfare. Many parents now helmet their kids, but not themselves. They should be easy targets!

One PSA tried in the boating field shows a little boy wearing a life vest walking along a beach, while the voice-over talks about how the little boy is going out in the family boat with his parents. The boat is going to turn over. The happy thing is that the little boy has on a life vest, so he's going to be just fine... and then the parents come into the scene, without life vests, and the voice says "But he's going to lose his mother and father." There should be some way to adapt that theme. There are more PSA's on this disk.

Seniors: Very little has been done with this age group. They have specialized publications and organizations who are generally eager for material that is seniors-oriented. All parts of the body age, generally getting more brittle and less flexible. So there may be special needs for seniors' helmets, a subject that is just beginning to be explored by researchers, and on which we have no hard data. If the research indeed shows that seniors' brains age along with everything else, they may need helmets with less dense foam to accommodate a tendency to be injured at lower force levels than youngsters. The Consumer Reports article in 1994 did rate "softest landing" helmets, but the ones in 1997 and 2002 did not. For seniors, look for a helmet designed to protect against "mild" concussions, not just severe brain injuries. There are none on the market today that we are aware of.

Set your project goals and objectives

Once you know who your main target group is, and approximately how many of them wear helmets, set some project goals and objectives. Your overall goal can be somewhat general, stating your project's main purpose. It could be, for example: To improve bicycle safety in the community. However, your objectives should be very specific.

The best objectives are measurable; you need to know when you have reached your target. For example, if 2 percent of all cyclists in your target group wear bike helmets, one of your objectives might be to increase that number to 10 percent in one year.

By making sure that your objectives are measurable, you can avoid one of the pitfalls of safety campaigns: setting vague objectives and being unable to tell when--or if--they have been reached. Often, the people who run such campaigns must fall back on the old cliche that, "if it saves one life, it's worth it." The problem is that they have no way of knowing whether it has saved one life or done anything at all.

It's also important to set realistic objectives. A grandiose target may sound good until you fall far short. Then, it will hurt your future efforts to gather support.

Safe Kids USA offered these general objective categories for local helmet campaigns. The comments and specifics are ours.

1. Build campaign momentum.

One local study showed that bicyclists were not against helmets...few had thought about wearing them. This may be true in your community, too. When you begin your campaign, expect to meet lack of awareness and apathy. But if you start with a dedicated core group, you can build a campaign that can change things over time. Here's a possible objective regarding campaign momentum:

In one year, we will have a core group of ten key volunteers and the cooperation and backing of the local PTA, the medical groups, the police, the media, and key youth groups.

2. Raise awareness of bike injuries and head trauma.

One reason few people think about helmets is that few know the facts about head and brain injuries. As they learn how vulnerable they and their kids may be, bicycle helmet use will begin to make more sense. Here's a possible objective regarding awareness of head injuries:

In one year, a survey will show that 30 percent of the local residents know the basic facts about bike head trauma associated with bicycle crashes.

3. Increase helmet purchases through greater availability.

If few people want helmets, few will buy them. And bike sellers will not push items they can't sell. As you increase awareness, work to make sure helmets are available through bike shops and mass merchandisers. Here's a possible objective regarding helmet purchases:

In one year, local merchandisers will report a 50 percent increase in helmet sales.

4. Increase helmet use.

The purpose of all the effort is to increase helmet use, not just awareness or sales. If people buy helmets but leave them at home, that's not solving the problem. Therefore, it's important to measure use. Here's a possible objective regarding increased helmet use:

In one year, bicycle helmet use among our target audience will increase by 50 percent, as measured in on-road bike counts.

5. Improve helmet fit.

One of today's most serious helmet problems is that riders--kids in particular--are using helmets that have not been adjusted to fit them. If the helmet is skewed when you hit, there may be zero helmet between you and the pavement. That's not a pleasant thought. And the 1997 Harborview research shows that there is a significant problem with injuries to helmeted riders that the authors attributed to improper fit. A possible objective:

In one year field observations will show that more than 50 per cent of riders have helmets that fit well.

6. Reduce the number of bike injuries, especially head injuries and lessen the severity of head injuries.

While this is the real bottom line, it will be difficult to measure, especially in the early years of your project. But take heart! In the State of Victoria, Australia, as the helmet campaign grew, serious head injuries at hospitals fell by 30 percent.

It may be possible for your local hospitals to become involved and to report their head injury statistics. Here's a possible objective regarding bike injuries: In five years, emergency room admissions for bicycling head injuries will decrease by 30 percent.

Having clear goals and objectives will also help when you look for support. Donors are more likely to back your cause if you can demonstrate that you know both where you are going and how to get there.

Sample goal statements from North Carolina helmet campaigns

Here are goals and objectives from two campaigns submitted for funding to the North Carolina Division of Maternal and Child Health, Office for Prevention. Look them over and decide which objectives are most easily measurable, which are least measurable, and which would be useful in your campaign.Program 1:

Goal: To have fewer bicycle-related head injuries

Objectives:

1. By the end of the project, to increase by 30 percent parents' knowledge about bicycle-related injuries, bicycle safety, and helmet use;

2. By the end of the project to increase by 20 percent the number of children, ages 5-10, using helmets;

3. By the end of the project, to increase by 30 percent the availability of bicycle helmets; and

4. To display helmets and bicycle safety materials at a minimum of five community sites.

Program 2:

Goal: To promote the use of bicycle and skateboard helmets.

Objectives:

1. To make parents and the general public aware of the need for bicycle and skateboard helmet use.

2. To involve other agencies and civic organizations in an effort to assure the continuation of this project.

3. To significantly increase the use of bicycle and skateboard helmets (especially for children age 5-15).

4. To make effective low-cost helmets available through the provision of discount coupons.

Using a steering committee

Building a coalition

A successful large campaign requires the cooperation of many people. By forming a bicycle helmet campaign committee of five to ten members, you can assemble a core group to solicit donations, promote the project, find volunteers, and solve problems. An effective committee will work to assure a future for your campaign.

Select potential members carefully. In an important sense, your committee should be a coalition of people concerned with safety and you should recruit from a variety of sources. As a suggestion, consider active people from medicine; the local bike club; bike shops; the media; civic clubs; youth organizations; parent/teacher groups; the local health, fire, and police departments; safety organizations; and the local office of the AAA.

Keep your committee to a workable size; five to ten members is a good range. Having too many members can slow progress to a crawl. But having too few members will result in volunteer burnout, a situation in which your core group dissolves from overwork.

Holding successful meetings

Set your meeting dates well in advance, and plan on follow-up emails or phone calls to remind members of meeting times and locations. Work to make it easy and enjoyable for them to attend; and make sure they know their efforts are appreciated. With a committee of busy people, you may find it difficult to get everyone together at one time. Why not try regular breakfast meetings at a local cafe?

Keep your meetings brief and to the point. Always work from a well-developed agenda, emailed in advance.

Involving committee members

Email a brief progress report to members regularly. This will help them keep on top of things and feel a part of the project. It will also help keep your meetings short, since committee members will already have received the materials. If a committee member has no email, just print out the email message and mail it on paper!

Key Committee Members

Publicity: The person in charge of publicity should have a good feel for dealing with the press. If possible, pick someone who has a track record (including news clippings). They will put out all news releases and schedule appearances on TV and radio shows.

Sponsorships and donations: Securing money, goods, and services takes a special talent and the willingness to ask. Having key contacts in the community is important as well. Remember that in-kind donations such as printing services, design work, and helmets for prizes can be as valuable as money.

Volunteers: Your volunteer coordinator must be able to make the work look attractive and valuable to potential volunteers and should have contacts in service organizations and other groups. Further, they must know how to treat volunteers once they are recruited. A good coordinator can help keep volunteers active for years by giving them well-defined tasks and making sure they feel appreciated.

Programs: Once your project starts getting publicity, you will get requests for presentations. (But don't wait for the requests to come--solicit invitations to speak to various groups!) You need someone who can prepare a presentation, speak in front of a group, and find other speakers. They must prepare scripts or Powerpoint presentations for use by others.

Production: Getting materials produced takes a basic knowledge of computer graphics and word processing. While your materials need not be fancy (unless you plan a large printing budget), they should look good and make sense. Some materials can be purchased outright, or campaigns and organizations such as the Bicycle Helmet Safety Institute are willing to let you reprint their materials free for any non-profit use (see listings below). Most campaigns use copying donated on office photocopy machines. We have some info on this disk if you need materials in Spanish.

To make your progress report an easier task, use a PC database to produce labels or envelopes. Then you can prepare a one-page newsletter, make copies or print them, fold, staple, and label them, and get them into the mail in less than half an hour.

Don't underestimate the value of a regular update mailing. Half an hour of keyboarding every two weeks can pay off handsomely in increased participation and enthusiasm by your committee.

Delegation of tasks is another key to an interested committee and a successful campaign. Make specific assignments with realistic completion dates. Your committee serves you best when each member can take on an important and well-defined task, such as one of the duties outlined above.

4. Creating your campaign

This section is organized into the following topics:

- Choosing a time frame, deciding how long the campaign will run, setting a timetable, finding funding and supplies,

recognizing volunteers and sponsors, evaluating your results and planning future campaigns.

- Choosing campaign messages - - Your basic message and support messages.

- Assembling the pieces of a campaign - - Creating displays, offering rewards for helmet use, cutting helmet prices,

making direct contacts, using the media, developing your publicity tools and distributing helmet promotion

materials.

If that sounds hard, check out how one community, Monroe County NY, has done it. They have an annual Wheel Sport Safety Awareness Contest. They provide a description of the contest and all the forms and documents they use, from a kindergarten coloring page to the form for a sixth grade essay, rap song or poem.

Choosing a time frame

Two excellent times for the primary campaign effort are early spring, when people are starting to think about bicycling, and fall, when students go back to school. Many helmet projects focus on these times.

But you don't have to limit your projects to these two seasons. The weeks before Christmas would be a good time for promoting helmets as presents. Mid-winter would be fine for a poster contest. Mid-summer would be a time to hand out prizes to cyclists seen riding with helmets, and is a popular time for police department bike rodeos because there are no school activities to interfere. Take advantage of each season's opportunities.

Deciding how long it will run

While your overall campaign can run for years and get better with the passing time, it's best to have a specific period for each year's main push. In order to accommodate a variety of activities, consider a time period of at least one week, but no more than a month. For example, if you plan to use discount coupons, give them an expiration date. This does two things: It makes retailers more likely to cooperate, since they know how long they will have to honor the discounts. And it improves response; in advertising, deadlines are well known for their ability to increase response because they force people to make a decision.

Setting the timetable

Establish a detailed timetable for your project, showing what needs to be done when, who is in charge, and who will help. By identifying each step, you can see which can become bottlenecks if not handled on time. For example, if you plan to give out helmet stickers, find out how much lead time your printer needs. Look over the sample time table shown below. While it isn't very detailed, it should give you a sense for how to create one for your campaign.

Finding money and supplies

Your next stop is to set a budget and start going after donations. You will probably buy some supplies and services, but in-kind contributions can provide for the bulk of your needs. List proposed cash purchases separately from expected donations. (See below for sample budgets.)

You may want one sponsor for your effort, or you may wish to attract several co-sponsors. By securing several sponsors, you reduce the amount required of each and you broaden the support base for your project.

Possible co-sponsors include recreation departments, police associations, the AAA chapter, bicycle shops, service clubs, medical groups, and insurance companies. But there is probably no more powerful sponsor than the local media: TV, radio or newspaper. Having a media sponsor ensures more coverage for your campaign than any other technique.

Most contributions will not come from your co-sponsor, but from many small donors. As examples, ask a local printer to print your brochures or a bike shop to contribute helmets for demonstrations. Many businesses are willing to donate photocopying.

Tracking down donations is a good task to delegate, but find someone who knows how to ask. Some people get easily embarrassed, hem and haw, and end up asking for "any contributions you could spare." Others mean well but are paralyzed at the thought of actually asking in person or on the phone. Occasionally you can find a person who is happy to solicit donations for your cause, and those people are valuable volunteers.

If you need two helmets, ask for them. Don't leave your prospective donor guessing. People are more likely to agree to specific requests than to vague (and possibly unlimited) ones. You may be surprised how easy it is to get those helmets!

Remind helpers that they aren't begging for donations, but are giving merchants an opportunity to participate in an important safety campaign. They should bring materials to show donors what the project is about and what they will gain from being associated with it.

Talk to potential donors early. Three weeks notice may be enough when asking for photocopying, but go after your major needs well in advance. For example, a local bicycle shop may be able to set aside some of last year's helmets for you IF you ask soon enough. If you want state or local foundation funding, find out what the funding cycle is. You often have to submit a grant proposal six months to a year in advance.

If you are running a more involved campaign, the Bikes 4 Kids program in Utah raised funding in 2006 for 1,000 bicycles, helmets, t-shirts and locks through sponsorships, a fundraising dinner with silent auction and bicycle rides, including a celebrity ride with Salt Lake City native Dave Zabriskie, the third American ever to wear the yellow jersey in the Tour de France. Some major charities use annual bike rides to raise funds, asking each participant to bring donations in. Adding a local celebrity can make it easier to recruit riders. The silent auction has proven successful for some local bike clubs, and in the case of the Washington Area Bicyclist Association has been combined with a cocktail party with formal wear in elegant surroundings to bring in an older and well-heeled group of donors.

Finally, be creative and resourceful. Remember, there is more than one source for everything you need and there are many ways to get what you want.

Sample Timetable

Task: Month: 1 2 3 4 5

Get background information X

Assemble core group X

Design campaign X X X

Set budget X X

Contact PTAs X

Meet with various groups X X X X

Raise money for campaign X X X X X

Buy videos X

Assemble press kits/fact sheets X

Contact bike dealers X

Contact TV, radio, newspapers X

Get TV spots X

Print discount coupons X

Distribute coupons in schools X

Contact bike dealers re: results X

Compile results X

Design next year's campaign X X

Recognizing volunteers and sponsors

It's a good idea to get your steering committee and other volunteers special t-shirts, pins, or caps. Such items will help identify them to the public, and will further add to their feeling of being involved.

You might plan a banquet or a special breakfast. And don't forget the "thank you" notes after they do a great job on a key task.

As often as possible acknowledge co-sponsors and each contributor in your printed literature or on your web page. During public events, mention sponsors and contributors over a public-address system. But strike a balance. If you go overboard, people may think your project is simply an advertisement.

Evaluating the results

If you've planned your campaign well, evaluating the results will be rewarding, useful, and relatively easy. By setting achievable, measurable goals, you will be able to tell if you've accomplished what you set out to do. Reaching your first year's goals can be a great boost for your second year. It can also give you plenty of useful information for news releases and fine-tuning your approach. Expect to make mistakes but learn from each one

Planning future campaigns

Your evaluation should give you a good idea of where you want to go next year and the year after. Start thinking about it immediately. Revise your goals and objectives. Then do some loosely-structured brainstorming sessions. Throw around ideas, regardless of how crazy they may initially seem. After you have plenty of ideas, refine the list into ones that you can accomplish and that meet your goals. Then, start planning your second year!

Choosing campaign messages

Your basic message

Your basic message should be, as stated by Safe Kids USA: "Wear a helmet every time you ride a bike."

This simple, clear-cut statement needs the support of detailed arguments about why one should wear a helmet. The first part of this manual should supply most of those arguments, while the references listed below and the suggestions given here will help to supply the rest.

In promoting this basic idea, keep in mind a famous rule of advertising: your message must ring true for your target audience. Even if your message seems true to you, if your target audience says "That's a lie!" you've lost whatever credibility you may have had.

Some helmet campaigns have used true statements that didn't seem true; and they lost their audiences. Others used statements that were closer to wishful thinking than truth ("Helmets look cool!" or "Everyone's wearing one!") and they lost their audiences too.

Barry Elliott, consultant to the best Australian helmet campaigns, says that "Successful communicators begin with a thorough understanding of the viewpoint of the audience. It is critical to know what can't be changed and what can be built upon,if we are going to encourage people to wear bicycle helmets."

An excellent way to decide among messages is to show them to a group of people in your intended target audience. Ask them which messages seem best, which not so good. Also you might ask them to come up with ideas of their own. This is your Focus Group, and they can be invaluable for checking changes and additions as the campaign progresses.

As you consider messages for your campaign, you should bear in mind that for most riders, a helmet is a piece of wearing apparel more than it is a safety device. It may be almost impossible to convince many riders that they will crash, but you can bet that a large percentage of them will be concerned with the way they look in a helmet. This applies to normal riders, not just vain people. Fashion sells more helmets than safety. You are a safety advocate, so you may not find that admirable or intuitive, but you can still use it to put together a successful campaign. The theme you are looking for should still have safety content, but if you are going to make use of the proven results from Madison Avenue you should also make the point that helmets make the rider look more competent, more intelligent, more thoughtful, more experienced on a bicycle, cooler and somehow much more attractive to the opposite gender!

Support messages:

Aside from your main message or slogan, you should have supporting statements that round out your campaign's theme. These can deal with a number of important side issues, like the following:

Looks and comfort:

- The new helmets are light, cool, colorful and comfortable

- Helmets make you look more competent, smarter and cooler

- Helmet prices have come down, down, down

- Helmets are less expensive than hospital care

- Helmets cost less than a pair of sneakers

- Helmets can last four or five years if they aren't crashed

- About 800 bicyclists die in crashes in the U.S. each year

- About 680 deaths could have been prevented by helmets last year

- Nearly 75% of all cycling deaths are due to head injuries

Here is a sample outline for a helmet talk to school kids or other groups. It is easy to adapt to different age groups.

Popular helmet campaign messages

Here are some messages used in various early helmet campaigns. In today's environment most of them seem to lack something: that spark that really catches your attention and provokes action. Some are certainly better than others but all of them can give you ideas. Some are also taken from commercial products. Rather than copying them, use these messages to spark your own creative process and develop something that seems less like old 20th century stuff. When you hit on a better one, send it to us to put in this list for the next reader!

Kids:

"Are you cool enough to wear a helmet?"

"Use your head...use a helmet."

"Don't knock yourself out on a bicycle. Get a bike helmet today!"

"O.S. Cat says...Wear a helmet every time you ride a bike! He is One Smart Cat!"

"Helmets are for cyclists who think for themselves...and want to go on thinking."

"Protection: you're not born with it. Wear your bicycle helmet"

"Protect your head - Wear a helmet!"

"Keep your brains where they belong: In your head!"

"Get the hard-head safety habit. Smart kids wear bike helmets."

"I don't want you to end up like me, please wear a helmet." (boy in wheel chair)

"Don't be a street stain. Wear your helmet."

"Wear a helmet....it won't kill you!"

"Your head is not as hard as you think it is."

Parents:

"Your child's head is not as hard as you think it is."

"Protect your child with a bike helmet."

"Parents are Precious Too - Wear a Helmet"

"Dear Parent...Do your kids need bicycle helmets?"

"Be bike smart. The child in your life depends on you for a lifetime of health."

"Heads you win."

"Do your kids need a bicycle helmet?"

"Protect your child from head injury."

Adult bicyclists:

"Friends don't let friends ride ignorant!"

"Keep your head in a safe place...wear a helmet."

"Be a well-dressed cyclist - wear a helmet."

"Bike helmets: the smart choice."

All ages:

"No helmet, no brains!"

"Get your head into a bike helmet."

"Get into the helmet habit."

"Buy a helmet - and wear it!"

"It never hurts to be in style. Get your head into a bike helmet."

"Bike helmets make safety sense."

"Bike helmets: the smart choice."

"Bicycle helmets: For your head's sake...show your good sense...buy and wear a helmet today!"

"Bicycle helmets: Do you use your head?"

"Protect your head. Where would you be without it?"

"Bike helmets - Don't hit the road without one."

"Bike helmets make sense."

"If we could predict when accidents are going to happen, there wouldn't be any!"

Public Service Announcements

These come from Valodi Foster, of the California Department of Health Services.

10-Second Spot

So your teen won't wear a bike helmet? Remind him or her that wearing a helmet correctly every time is responsible behavior...the same kind needed to drive the family car at 16.

10-Second Spot

So your child won't wear a bicycle helmet? Remind him or her that wearing a helmet correctly every time is responsible behavior...the same kind needed to earn that new privilege he has been asking for.

15-Second Spot

It's a fact. Approximately 900 people, including more than 200 children, are killed annually in bicycle related incidents nationwide, and about 60 percent of these deaths involve a head injury. The good news: (pause) research indicates that a helmet can reduce the risk of head and brain injury by 63 to 88 percent. Use your head. Use a helmet.

A message brought to you by (name of local organization).

15-20 Second Spot

So you've heard that 60 percent of all bicycle deaths involve a head injury, and now you want to buy a helmet. The problem is, you don't know what kind of helmet to buy. As of March 1999, all helmets are required to meet a standard set by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission that ensures adequate protection of the head. Now you know. So what are you waiting for? Get your helmet today!

A message brought to you by (name of local organization).

15-20 Second Spot

You've bought the helmet for your kids, and now it's time to enjoy the beautiful weather and start riding those bikes! But your child won't wear the helmet. So ride with your kids and wear your helmet too! Kids tend to model what their parents do. So if you want your children to practice good bicycle safety, make sure you practice what you teach!

A message brought to you by (name of local organization).

30 Second Spot

Hi, I'm Officer [NAME] of the [STATE/LOCAL] police department. Too often I've seen the tragedy of children seriously injured or killed in bicycle crashes simply because they weren't wearing a bicycle helmet. I've seen the devastating effect it has on families and on the community. We can prevent these senseless deaths. That's why law enforcement across [STATE/CITY] are out, right now, enforcing [STATE's] bicycle helmet laws. No warnings. No excuses. So do your job, or I'll do mine. Make sure your children wear their helmet each and every time they ride their bikes. There's just too much to lose.

A message brought to you by (name of local organization).

30 Second Spot

Hi, I'm Officer [NAME] of the [STATE/LOCAL] police department with a safety tip we can all live with. It's simple...make sure your children wear their bicycle helmets. Every year I see too many children seriously injured or killed in bicycle crashes. In fact, bicycle crashes are the leading cause of death and injuries among children 5-14. I'm working hard to prevent these senseless deaths...but I need your help. There's just too much to lose.

A message brought to you by (name of local organization)

30 Second Spot

What protects children, saves lives and saves taxpayers millions? Wearing a bicycle helmet. In fact, if every child in [STATE] just put on a bicycle helmet, we would save the lives of more than [XXX] children next year alone. Plus it would save taxpayers [$XX] in health care and insurance costs. So make sure your children wear their helmets and support stronger enforcement of [STATE'S] bicycle helmet law. There's just too much to lose.

A message brought to you by (name of local organization)

A Longer Dialogue

"Just in Case"

Mark: Hey Joe, let's ride our bikes and go get some baseball cards.

Joe: Okay, let me go home to get my bike.

Mark: You don't have to go all the way home, just use my brother's bike. He won't mind.

Joe: Even if I did use your brother's bike, I'd still have to go home and get my helmet.

Mark: (Laughing as he starts to tease Joe) Helmet? Aw c'mon. Those things are for little kids. You can ride a bike just fine. You don't need a helmet. Let's just go.

Joe: Sorry, Mark, can't. What if something weird happens. I'd rather be safe than sorry.

Mark: You make it sound like riding a bike is dangerous.

Joe: A report I had to do for school made me think about it. In (name of state) (xxx amount) of people have been really hurt and that (xxx amount) of people have been killed in bike crashes. Even if you do survive a crash, a serious injury can lead to permanent problems. I know I don't want to end up having my mom helping me every time I have to do simple things, like eating or using the bathroom. I don't know about you, man, but I'd rather wear the helmet just in case.

Mark: Well. . . . .okay. . . .. .you go do what you have to do. When you're ready, come get me in my room.

Joe: In your room? I thought we're riding to the card store? Why don't we meet at the corner like we usually do?

Mark: Because it's gonna take me at least 15 minutes to find my helmet in my closet!!

Joe: (Laughing) Oh, okay. I'll be back in 15 minutes.

Narrator: Use your head. Use a helmet. After all, it's your head.

Mark: Hey Joe, let's ride our bikes and go get some baseball cards.

Joe: Okay, let me go home to get my bike.

Mark: You don't have to go all the way home, just use my brother's bike. He won't mind.

Joe: Even if I did use your brother's bike, I'd still have to go home and get my helmet.

Mark: (Laughing as he starts to tease Joe) Helmet? Aw c'mon. Those things are for little kids. You can ride a bike just fine. You don't need a helmet. Let's just go.

Joe: Sorry, Mark, can't. What if something weird happens. I'd rather be safe than sorry.

Mark: You make it sound like riding a bike is dangerous.

Joe: A report I had to do for school made me think about it. In (name of state) (xxx amount) of people have been really hurt and that (xxx amount) of people have been killed in bike crashes. Even if you do survive a crash, a serious injury can lead to permanent problems. I know I don't want to end up having my mom helping me every time I have to do simple things, like eating or using the bathroom. I don't know about you, man, but I'd rather wear the helmet just in case.

Mark: Well. . . . .okay. . . .. .you go do what you have to do. When you're ready, come get me in my room.

Joe: In your room? I thought we're riding to the card store? Why don't we meet at the corner like we usually do?

Mark: Because it's gonna take me at least 15 minutes to find my helmet in my closet!!

Joe: (Laughing) Oh, okay. I'll be back in 15 minutes.

Narrator: Use your head. Use a helmet. After all, it's your head.

-------------------------------------------

Valodi Foster, MPH

vfoster@dhs.ca.gov

A PSA Available on the Internet

If you connect to the Brain Injury Association of Minnesota website at www.braininjurymn.org/Media/bully.htm you will find a full-blown PSA in .mpg file format. It's a big file (9 megs), with sound and picture ready to go. For info on using the .mpg, please use the contact info on the site.The PSA shows a kid riding along a neighborhood street when a bully rides alongside, harassing him about his sissy helmet. As they ride, the bully is not paying attention to where he is going, and he suddenly collides with a board sticking out the back of a truck parked in a driveway, ending the PSA. It is quite a shock, and most people will never figure out that the bully got hit in the face with the board, and a normal bike helmet would not have protected his face anyway.

5. The pieces of a campaign

The most effective helmet campaigns combine a number of important elements. It has been said that a campaign that uses only one approach will probably fail. Consider the following when putting together your package and keep your target group firmly in mind.

Creating displays

Try to put your message where many people gather or pass by. Create a list of as many of those places as you can. Here are some ideas.

Window displays

Many businesses allow groups to use their windows for public service messages. The problem, initially, will be to find enough materials to make the displays look interesting. One approach would be to start with a helmet poster contest and use the entries in your displays.

Changeable signs

In commercial strip-type areas, many businesses will allow use of their changeable signs for public service messages. Keep the message simple (use your campaign slogan) and you may get it up all over town!

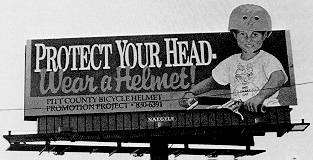

Billboards

Several communities have used large billboards to get across bicycle safety messages. The helmet campaign in Pitt County, North Carolina, for example, used one to promote helmet use among kids.

Another community, Cranford, New Jersey, hung a large banner from an overpass that spanned one of the busiest roads in town. Nearly everyone got the message.

Stand-alone displays

If you have a talented designer or carpenter, consider building a standalone display that can be moved around to different schools, the malls, medical centers, and public buildings. While flat vertical surfaces that hold posters are about the easiest to put together, other displays might be more interesting for the viewers. Here are a few things you might incorporate into a display:

- Broken helmets with the owners' crash stories

- X-rays of skull fractures

- Posters showing well-known people wearing helmets

- Colorful helmets that people can try on for a look in a mirror (hook the helmets to the display with a small cable)

- Student helmet posters

Places for displays:

- Doctors' offices

- Dentists' offices

- Health Clinics

- Hospitals

- Health clubs

- Convenience stores

- Department store bike sections

- Video arcades

- Baseball card stores

- Fast food shops

- Bike shops

- Malls

- Computer game stores

- Magazine and book shops

- Bank lobbies

- Insurance offices

- Downtown shop window displays

- Record stores

- School lobbies

- Campus cafeterias

- City and county offices

- Park bulletin boards

- Police departments

- Fire departments

- Swimming pool bulletin boards

- Busy plazas (especially covered ones)

Rewards for helmet use

Another popular way to promote bicycle helmets is to reward those who currently wear them. Often, these cyclists get teased by friends who don't wear helmets; this is especially true of young riders. Here are some ideas that have been used around the country.Prizes for Schools

In one campaign, elementary schools were given blank posters on which to paste pictures of students who wore helmets. The schools with the largest proportions of helmeted bicyclists won prizes, as did the students. Helmets are a natural part of any "ride your bike to school day," of course, fitting in well with campaigns to reduce obesity. Another idea for emphasizing bright clothing is a day to award "Best and Brightest" prizes to those with the brightest clothing and helmets.

Coupons for wearers

During one city's campaign, cycling superheroes Sprocketman and Sally Streetwise patrolled the street rewarding bicyclists for wearing their helmets. Cyclists received their choice of movie tickets, video game tokens, or ice cream gift certificates. Local merchants donated the prizes and members of the bicycle club performed the superhero roles.

Cutting helmet prices

Even though helmet prices in discount stores are low, there is little doubt that cutting the prices of bicycle helmets can boost sales. Parents may be hard-pressed to buy helmets for their entire family. Prices may not have fallen as much in less competitive markets. And, of course, everyone loves a bargain, which can motivate a purchase far beyond the actual money saved.

There are a number of possible approaches.

Discount coupons

You can distribute discount coupons in several ways. One is the approach used in Missoula, Montana (see the Case Study in Appendix 6H below). They got all the local bike shops to offer discounts on helmets and printed the prices on coupons distributed through the schools. Shop owners were asked to keep the redeemed coupons and turn them in at the end of the three-week Spring campaign. Counting redeemed coupons told campaign officials how many helmets were sold.

Further, Missoula used the names from the coupons for a follow-up survey six months later. The discounts came out of the dealers' profits; however, since campaign planning started the previous fall, shop owners were able to secure good prices on the helmets they discounted. Since that campaign, prices have fallen to the point where dealers can now find good quality helmets for dealer prices of under $10 each. Even at normal bike shop markups, that should yield a final price to the consumer of about $15. Although this may be more than your local discount store, and more than you can arrange through a direct buy campaign, the help offered by good shops in fitting the helmets they sell can make the difference worthwhile.

Another approach with discount coupons is the one used in Madison, Wisconsin. They published the coupons in local newspapers and customers could buy helmets at discount prices at the shops listed. In this case, the shops also bore the cost of the discounts. On a smaller scale, a Pennsylvania bicycle club put several hundred dollars towards $5.00 discounts on helmets bought at a local bike shop.

The State of Oregon, in participation with helmet manufacturers and retailers, offered helmet discount coupons to youngsters who created helmet posters at mall-based activities around the state.

A December holiday season discount coupon published in local newspapers can motivate grandparents and others to give helmets as holiday gifts.

Low retail prices